Let’s return to Kansas and look at another aspect of farm life. (It might be easier to follow if you start with the post for make-ahead cocktail meatballs.)

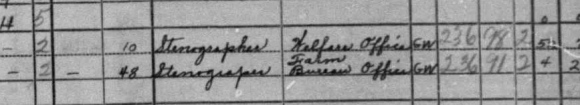

This recipe says it’s from Opal Knight. I think I’ve found the right Opal Knight in the census. If you’re curious, in 1940, Opal had most recently worked as a stenographer in the farm bureau office and was a year older than the owner of the recipe box, F.J.

Since F.J.’s soon-to-be husband was an agricultural worker, it’s possible she knew Opal through him.

The Kansas Farm Bureau is a nonprofit advocacy organization that protects the interests of farmers and others who make their living through agriculture. In the years leading up to and through World War II, it faced some challenges people generally don’t remember.

Although we think of the draft as a wartime measure, the draft of men who would ultimately serve in World War II began in October 1940. In November, at the Kansas Farm Bureau’s state convention, the members adopted a resolution, as reported in the November 10, 1940 edition of the Hutchinson News Herald:

|

A strong declaration was made “that we should do everything possible to keep from being involved in foreign wars now in progress,” and add:

“American blood should not be shed on foreign soil on account of quarrels that do not concern us. We should never again send our boys away to die for a cause that is not ours and in spite of anything we can do will only be continued through the years.” But the Kansas Farm Bureau adds: “As a means of protection to our country and our people, we favor an adequate and efficiently administered plan of defense. We believe by centering our energy on preparedness that we can keep our boys at home, and save our democracy for ourselves and our posterity.” |

Of course, Pearl Harbor changed that, next year. But entering the war created its own series of problems.

We discussed in the make-ahead cocktail meatballs post that Roy E. Jones was classified as II-C, or an essential agricultural farm worker, in 1944. While that classification existed throughout the war effort, there was a perception among some people that an able-bodied man working on the farm might be doing it to avoid serving. Between 1940 and 1942, about six million farm workers left, either to enlist or take factory jobs.

But a manpower shortage was not the end of the issue. While labor-saving devices could have replaced some of the workers, the rationing of steel and machinery made it very difficult to repair existing machinery. The factories that would’ve produced more machinery were either idle due to lack of material or converted to the war effort.

From the same newspaper, on November 5, 1942 (Dr. O. O. Wolf was the farm bureau president at the time):

|

Dr. Wolf told the farmers that America could win or lose the war right on the farm front. More than 3600 Kansas farms will stand idle next year and that, together with idle land on farms only partially producing, will take an estimated 193,000 acres out of production next year, he predicted.

“Adjustments are necessary to win the war and agriculture can make its best contribution by using every available manhour of work possible,” he concluded. |

Or even womanpower, as the case may be. From the next day’s paper:

|

The Kansans studied the proposal then agreed it would be hard to attract town women to the farm as hired men. Married women mostly have households to look after and the unmarried women are grabbing up jobs in defense plants.

E.W. Franzke, Kansas director of the U.S. employment service, argued work in a large defense plant with pleasant surroundings and at high wages had dramatic appeal, but he doubted if many women could be induced to replace men at doing chores and field work–that is, women who don’t already live on the farm. One representative of the dairy industry asserted women might relieve the labor shortage to a certain extent but doubted if it would be worth training them. Dr. O. O. Wolf of Ottawa, president of the Kansas farm bureau, said students, women and business men were being utilized successfully in some areas where there is sufficient supervising personnel. |

Well, skeptical or not, in 1943, we reactivated the Women’s Land Army of America.

In World War I, there was no agricultural exception to the draft, and women had been recruited into the Women’s Land Army of America (so called to distinguish it from the original in Great Britain). So in 1943, more than a million women were recruited and trained to perform farm tasks. They were paid as “utility men,” which is to say, unskilled laborers, making between 25 and 40 cents and hour–enough to find lodging and buy farming clothes. But like many people, they did the job to help the war effort.

The program continued until 1947, although some women stayed on as volunteers thereafter. Today, when we picture women working during World War II, we tend to picture Rosie the Riveter. But just as the Kansas Farm Bureau observed in its 1942 meeting, the factory seemed like a dream job compared to some of the tasks on the farm.

For the history of fudge from its origin in Baltimore to the 20th century, visit the post for fudge from the box of A.D. from Lutz, Florida.

From the box of F.J. from Sun City, Arizona. Some cards suggest a family history in Missouri and Kansas.

Chocolate Fudge

2 c. sugar

2/3 c. milk

1 sq. chocolate or 3 Tbsp. cocoa

2 Tbsp. corn syrup

2 Tbsp. butter

1/2 tsp. vanilla

Boil sugar, milk, and chocolate to a rather soft ball stage.

Remove from fire; add vanilla and butter and let cool until a consistency of molasses.

Beat until creamy, add nuts and pour into buttered tins. Don’t smooth top with a knife.

Do not pour until it begins to hold its shape.

Opal Knight